Pages: 15-22

“In science, you have to live long, then something will work” — this is how I would like to paraphrase the words of Korney Chukovsky, said by him on his 80th birthday. It would seem that on the threshold of your eightieth birthday, it is difficult to resist the temptation to collect all your books in a heavy pile and decide that this was your life, which has been lived to the fullest. Then you should feel deep satisfaction. But this feeling for our hero of the day, fortunately, is unavailable.

Valentin is in a hurry to do everything faster (“I’m Dergachev, it means “rushy” I hear since the day we met in 1996) to make room for other study, new one and more enjoyable. Now it may seem that this is a feature of a person in his declining years who is afraid of not having time to do something or, instead, not having time to finish something. But looking at the drawings, diaries and reports by V. A. Dergachev, one can say that this temperament was always inherent in him, starting with his first steps in archaeology. Although, even in his eighties, Valentin Dergachev, at this completely insane pace, finds time to enjoy scientific research. Therefore, V. A.’s colleagues still have the rare pleasure of watching the scientist in the process of creating a database, processing illustrations, or restoring pottery.

Over many years of scientific work, in one way or another, the style of presenting the research develops itself. But Valentin’s style of is so original that sometimes it resembles the way of communication of a 52 hertz whale or the famous “lone whale”, who tries to communicate with congeners on a frequency of 52 Hz, known only to him. But the thing is that the maximum frequency that blue whales perceive is ten to twenty hertz lower. At the same time, the whale is a sizeable self-sufficient organism, and the Pacific Ocean where it lives is so boundless that any possibility of communication with representatives of its own species is reduced to zero. In addition, Dergachev uses only methods that he fully understands. Sometimes those that only he understands, according to his opponents. But this, it seems, does not bother Valentin at all. Just like a whale that keeps passing tons of water through itself in search of food, in Dergachev’s case — for thought.

Over many years of scientific work, in one way or another, the style of presenting the research develops itself. But Valentin’s style of is so original that sometimes it resembles the way of communication of a 52 hertz whale or the famous “lone whale”, who tries to communicate with congeners on a frequency of 52 Hz, known only to him. But the thing is that the maximum frequency that blue whales perceive is ten to twenty hertz lower. At the same time, the whale is a sizeable self-sufficient organism, and the Pacific Ocean where it lives is so boundless that any possibility of communication with representatives of its own species is reduced to zero. In addition, Dergachev uses only methods that he fully understands. Sometimes those that only he understands, according to his opponents. But this, it seems, does not bother Valentin at all. Just like a whale that keeps passing tons of water through itself in search of food, in Dergachev’s case — for thought.

“My name is Valya”

He is considered a late entrant to science. After college and the army, working years in commerce, he entered university late by today’s standards. But this is not entirely true. As he recalls, Dergachev’s interest in the expedition romance and exotic travels appeared when he was ten and was taught to use the school library. Already studying at the college, he regularly visited the Museum of Local History for numismatic consultations with A. A. Nudelman. Later, the collection of coins had to be parted with when it became clear that collecting antiquities was incompatible with the profession of the archaeologist. But before that, in the early 1960s, while working in commerce, he bought a bicycle and regularly visited the Moldavian fortresses and reserves.

V. A. Dergachev spent his first real archaeological season with V. I. Markevich on the Varvarovka (Vărvăreuca) settlement. Then he participated in the excavations until late autumn in the Soroca fortress. Already in the winter, while the impressions were fresh, he wrote an article for the “Soviet Trade” journal about the history of pottery, starting with the Trypillia culture, but then the publication was rejected. In 1971, during the study in Petersburg, it became clear why. The journal sent it to the Institute of Archaeology for review, and the article first got to T. S. Passek, who passed the text to E. K. Chernysh (both great scholars in Trypillia). Still the latter did not like the presented version of the appearance of ceramics. V. A. Dergachev published his first scientific article in 1964 about the early Slavic settlement of Starye Malaeshty (Mălăieştii Vechi) after an expedition season with P. P. Bîrnea.

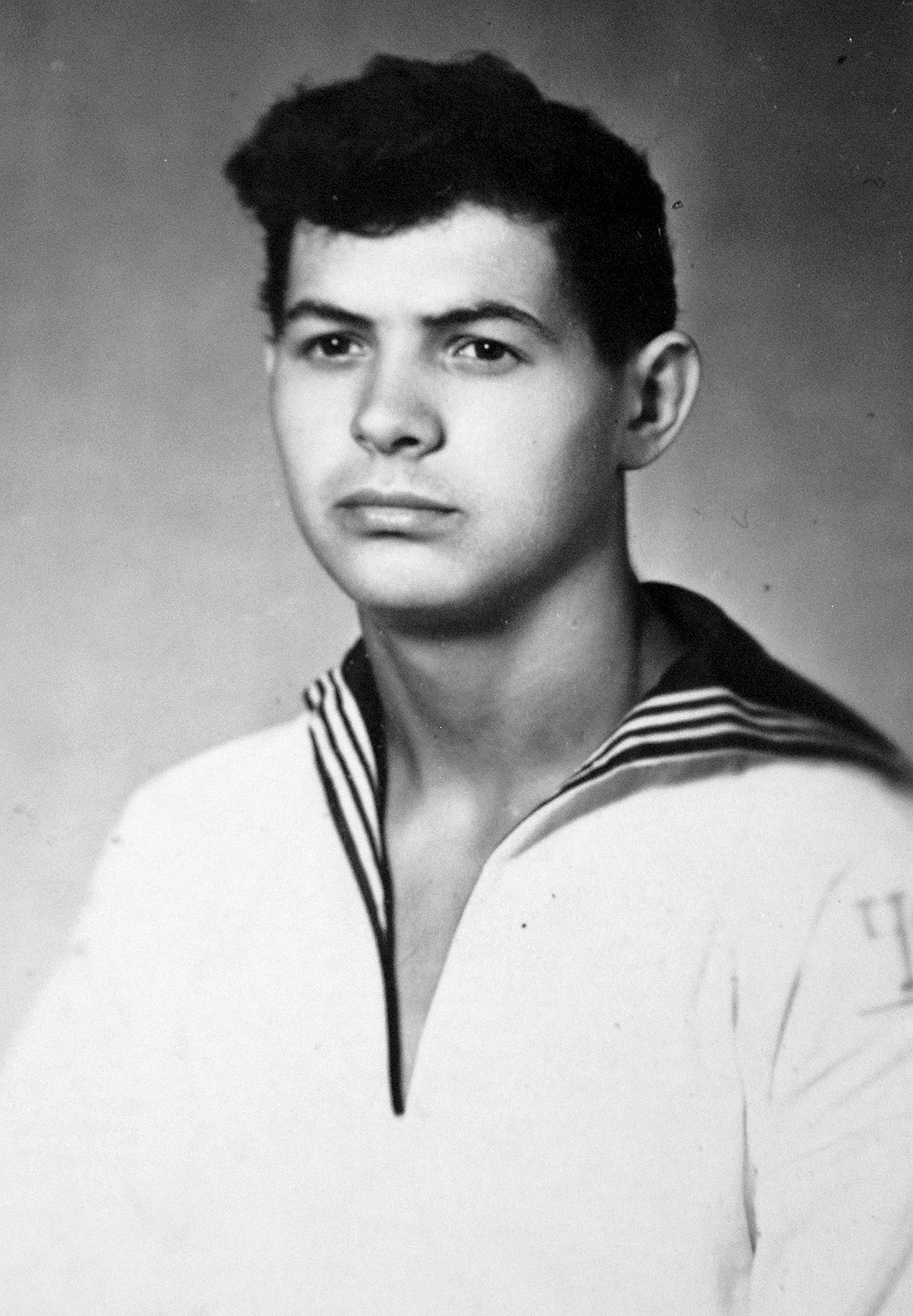

One of the expeditions of the early sixties, led by Vsevolod Markevich on the Trypilian settlement at Novye Ruseshty (Ruseştii Noi) in 1963 was also reflected in journalism. “A handsome tanned guy, shirtless and wearing a strange cap devoid of a visor… with a soft Moldavian accent”. “My name is Valya, I am Markevich’s deputy” And Valya — “he looks like he has just been to the Trypillia time, he knows everything about it” (Сухарев 1963: 14—15). And although hero’s name in the essay does not appear immediately, it is hard not to recognize Valentin Dergachev in this “guy” even now, sixty years later. At that time, he was twenty. The conversation turned to education, “Valya” replied: “I have a different speciality. I’m actually a cook. I am working in a dining car of the Moscow-Kishinev train. Well, as for the season starts, I join the archaeological expeditions, the third year already. Expeditions are from spring to late autumn, so I go from one to another. I was excavating the Slavs, the Scythians… But still, — he raises his eyes — I firmly decided: I will specialize in Trypillia, like Vsevolod Markevich” (Сухарев 1963: 15).

One of the expeditions of the early sixties, led by Vsevolod Markevich on the Trypilian settlement at Novye Ruseshty (Ruseştii Noi) in 1963 was also reflected in journalism. “A handsome tanned guy, shirtless and wearing a strange cap devoid of a visor… with a soft Moldavian accent”. “My name is Valya, I am Markevich’s deputy” And Valya — “he looks like he has just been to the Trypillia time, he knows everything about it” (Сухарев 1963: 14—15). And although hero’s name in the essay does not appear immediately, it is hard not to recognize Valentin Dergachev in this “guy” even now, sixty years later. At that time, he was twenty. The conversation turned to education, “Valya” replied: “I have a different speciality. I’m actually a cook. I am working in a dining car of the Moscow-Kishinev train. Well, as for the season starts, I join the archaeological expeditions, the third year already. Expeditions are from spring to late autumn, so I go from one to another. I was excavating the Slavs, the Scythians… But still, — he raises his eyes — I firmly decided: I will specialize in Trypillia, like Vsevolod Markevich” (Сухарев 1963: 15).

“Machine for obtaining scientific results”

“You see, what strange ways sometimes come to our science,” says Georgy Smirnov, archaeologist… Valya Dergachev is a cook. He was recently promoted to manager of a restaurant. The salary is one hundred and fifty rubles. But he comes to us for fifty and even works from dawn to dusk…” (Сухарев 1963: 15). Valya the cook will be an archaeologist, there is no doubt, concludes the author of the article in 1963. And he was absolutely right. In 1966, our hero of the day finally left professional cooking and becomes a professional archaeologist — an inspector of the Society for the Protection of Monuments of History and Archaeology, enters the Kishinev State University. And in 1973, he got a job at the Moldavian Academy of Sciences, where he will work until his retirement, including almost twenty years as director of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (since 2005 — the Institute of Cultural Heritage). “Ran his career to the highest position in the region as a meteor” (Клейн 2018: 323).

In 1969—1973 starts Dergachev’s “Petersburg period” at Leningrad University, where his professors included prominent world-class scholars. Among them where M. I. Artamonov, B. B. Piotrovsky, P. I. Boriskovsky, V. M. Masson and L. S. Klein. A decade ago, Leo Klein recalled that “the lively and energetic Moldavian guy immediately caught his attention” (Клейн 2013: 19). Then, at the Leningrad State University, at the Department of Archaeology, there were various internships. But Dergachev chose a different path: he transferred to Leningrad University at the Department of Archeology from the fifth year to the second. “He immediately stood out among other students by the fact that he began to have printed works published every year” (Клейн 2013: 19). Including two monographs — “Sites of the Bronze Age” in the series “Archaeological Map of Moldova” and “Bronze objects of the 13th—8th centuries BC”. It sounds weird now, but before the release of these papers, it was believed that there were almost no Bronze Age metal objects in Moldova, especially in the hoards. In fact, no one was interested in it. And after the publication of the hoard from Hristici, Dergachev began to respond to all the signals received about such finds to go to the place of discovery, to visit dozens of regional and school museums.

In 1969—1973 starts Dergachev’s “Petersburg period” at Leningrad University, where his professors included prominent world-class scholars. Among them where M. I. Artamonov, B. B. Piotrovsky, P. I. Boriskovsky, V. M. Masson and L. S. Klein. A decade ago, Leo Klein recalled that “the lively and energetic Moldavian guy immediately caught his attention” (Клейн 2013: 19). Then, at the Leningrad State University, at the Department of Archaeology, there were various internships. But Dergachev chose a different path: he transferred to Leningrad University at the Department of Archeology from the fifth year to the second. “He immediately stood out among other students by the fact that he began to have printed works published every year” (Клейн 2013: 19). Including two monographs — “Sites of the Bronze Age” in the series “Archaeological Map of Moldova” and “Bronze objects of the 13th—8th centuries BC”. It sounds weird now, but before the release of these papers, it was believed that there were almost no Bronze Age metal objects in Moldova, especially in the hoards. In fact, no one was interested in it. And after the publication of the hoard from Hristici, Dergachev began to respond to all the signals received about such finds to go to the place of discovery, to visit dozens of regional and school museums.

His performance is legendary. “He is a fanatic; he was ready to talk passionately for hours about typology and all kinds of categorization of material” (Добролюбский 2013: 291). Even in the most challenging moments of his administrative career, V. A. Dergachev continued to design illustrations, maps, refe¬rences and smoke without being distracted by court intrigues, usually, lighting the next cigarette from the previous one and drinking strong tea.

“More lasting than bronze”

Dergachev had once been predicted the main features of his life — fear of drafts, an abundance of money and constant travel. The latter would have especially pleased the country boy, who read about the Central Asian expeditions in the school library. But now he writes books and travels with his lectures all over Europe — in Cambridge, Berlin, Heidelberg, Freiburg, Saarbrücken, Liege, Poznań, Budapest etc.

“I firmly decided: I will specialize in Trypillia ,” says Valentin back in the distant 1963. Although most of Dergachev’s papers are devoted to metal objects of the Bronze Age, the most elegant and thunderous book is “Sites of late Trypillia”, which is the most successful systematization of the vast array of data on the sites of the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture. The basis of this book is a PhD thesis presented in 1979 in Leningrad. In 1990, V. A. Dergachev defended his “Moldova and neighbouring territories in the Eneolithic-Bronze Age” habilitation thesis, which will turn into one of the essential books of Moldavian archaeology. At the same time, one of his teachers, Leo Klein, considers Dergachev’s best work to be “On sceptres, on horses, on war” even though Klein criticized it and rejects all the conclusions. After all, for this book, Valentin “developed and applied many brilliant methodological techniques, did the most sophisticated studies, obtained very interesting data in very labor-intensive operations, which will more than once serve for completely different studies” (Klein 2013: 20).

It is no coincidence that this volume is titled with a line from Horace, who discourages Melpomene by saying that “he built a monument more lasting than bronze”. Though what could be more robust than bronze and more transient than monuments? In this sense, the fate of monuments, in whose protection Valentin Dergachev worked in his youth, is similar to the destiny of many scien¬tific texts. They are often demolished, sent to the trash, or melted into new ones. At the same time, bronze or even copper, which Dergachev is so passionately engaged in throughout his career, has lived in human culture for thousands of years. So do good scientific texts, which, as a rule, outlive their creators for a long time and become the foundation for the discoveries of the next generations. Especially if the texts, like metal objects, are covered with a noble patina.

References:

Dobroliubskii, A. O. 2013. Odesseia odnogo arkheologa (OdEssey of an Archaeologist). Kyiv: “Oleh Filyuk” Publ. (in Russian).

Klejn, L. S. 2010. In Stratum plus. Archaeology and Cultural Anthropology (2), 315-321 (in Russian).

Klejn, L. S. 2013. In Revista arheologică 9 (1), 19—20 (in Russian).

Klejn, L. S. 2018. Dialogi. Teoreticheskaia arkheologiia i ne tol’ko (Dialogues: Theoretical Archaeology and Not Only). Saint Petersburg: “Evraziia“ Publ. (in Russian).

Sukharev, D. 1963. In Smena (Smena) (2), 12—15.

Information about author:

Denis Topal (Kishinev, Moldova). Doctor of History. National Museum of History of Moldova. 31 August St., 121a, Chişinău, MD-2012, Moldova

E-mail: denis.topal@gmail.com

ORCID: 0000-0002-8586-4427